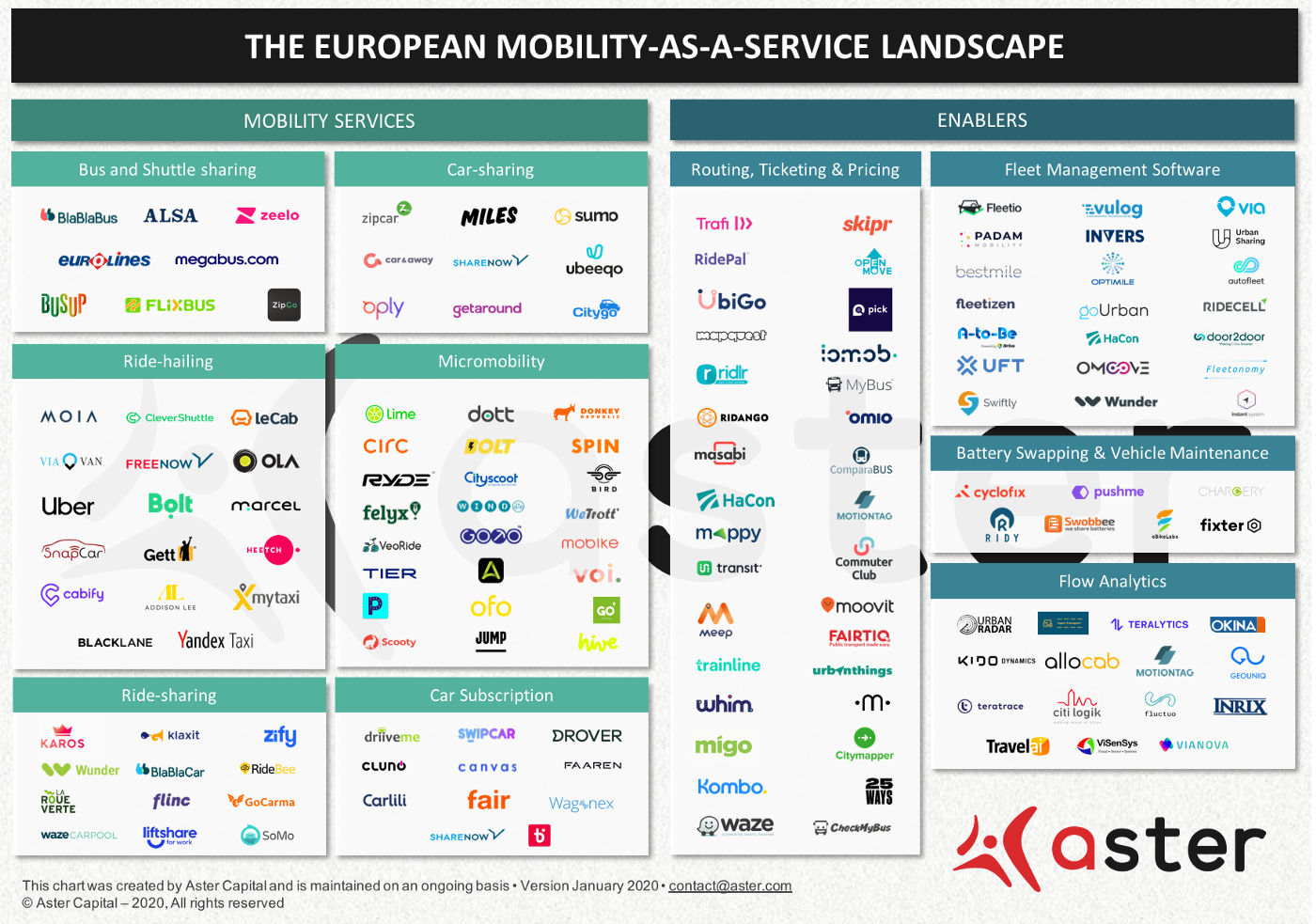

We’re in the midst of an exciting paradigm shift in the world of mobility.

Just a few years back, there were only a few methods of getting around cities, including bikes, personal vehicles and public transportation. Today getting from A to B is increasingly personalized. Building on traditional transportation options, now on-demand ride hailing, innovative car subscription services and free-floating micromobility offers are becoming commonplace. All of these new mobility offerings have sparked the rise of Mobility-as-a-Service (MaaS). If you’re not yet familiar with MaaS, here’s a good article to check out.

MaaS has become a trendy buzzword over the past few years, mainly due to its great potential to reduce car ownership and make urban transportation more sustainable. But looking beyond the hype, what are the assumptions and misconceptions about MaaS? Where can it add value?

Mobility being one of the areas we are passionate about here at Aster, we’ve studied up on the subject and want to share our take on four of the most common MaaS myths that we’ve come across.

Myth #1: Blitzscaling is a recipe for success in the world of MaaS

Investors have poured money into new modes of transportation in recent years, encouraging ride-hailing, e-bike and e-scooter startups to leverage a “Blitzscaling” approach, where speed is prioritized over efficiency in uncertain environments. Indeed, this strategy makes sense in a market where there is little to no brand awareness, network effect or even economies of scale. It’s about who raises the largest amount of money to be able to flood the market fast and kill out competition. And in times of large capital availability and Fear of Missing Out (FOMO), investors are often keen on backing up these models.

But blitzscaling has had some pitfalls in the MaaS market, where it has so far turned out to be more effective for burning cash than increasing market share.

In the ride-hailing market, Uber and Lyft have been spending massive amounts of money to compete over a few points of market share. According to Agence15marches, Uber at one point dedicated 55% of their revenue on promotions and other benefits, while Lyft spent up to 127% of its revenue on marketing prior to IPO. Even though private investors trusted Uber with $24.7 billion worth of equity and debt, its unsustainable business model is one of the main reasons the company saw its public valuation fall from an expected $120 billion to $82 billion on its IPO to $56.47 billion as of today (28/10/2019).

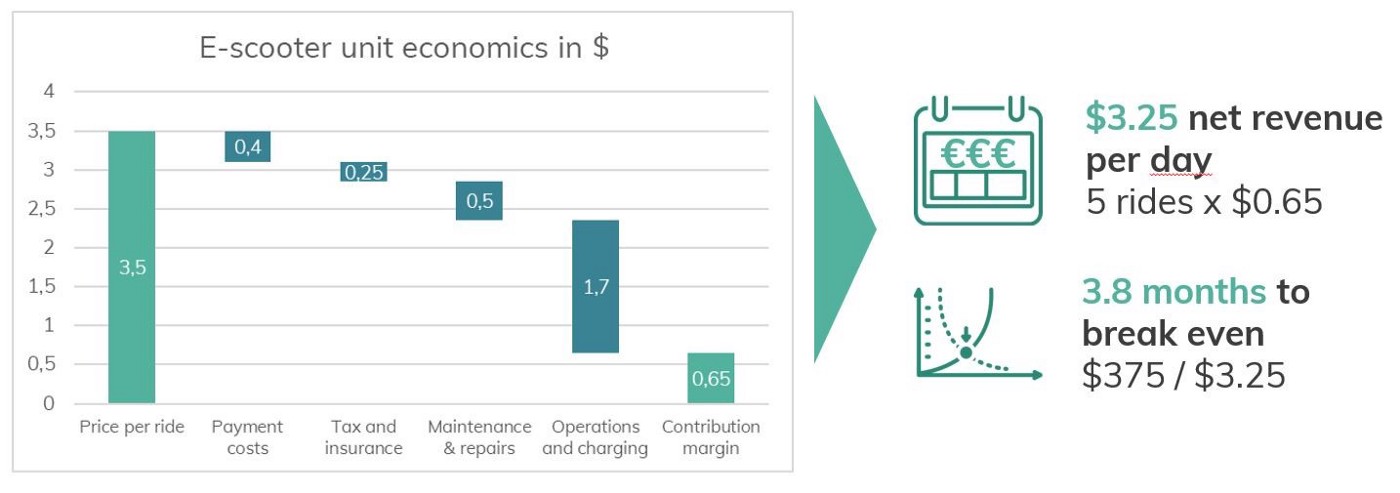

The downsides of blitzscaling can be also be seen in the micromobility segment. After raising $2.2 billion and flooding cities across the globe with bikes, Alibaba-backed Ofo backpedaled from international markets and is now fighting for survival as it struggles to pay back debts to users and suppliers. Ofo’s competitor Mobike has a similar story, announcing in March of this year it would be cutting operations from most international markets. This is without mentioning the negative externalities of such an approach.