Thursday, February 1st, Aster held its first edition of the Aster Open Tour, opening its doors to the players of new mobilities. Eight startups set up in our own offices met with a mostly corporate crowd – in accordance with Aster’s Business Hub approach. Axelle Lemaire, Former Secretary of State for Innovation and Digital Affairs, took part in the event.

Jean-Marc Lazard, CEO and founder of OpenDataSoft, and Jean-Marc Bally, Managing Partner of Aster, were live on BFM Business to talk about their partnership, how they met and their projects in common.

To watch the replay:

You may have heard the quite surprising story of a US start-up company counting cars in US retailers’ parking lots to estimate the quarterly earnings of retailers before they get released. What’s even more remarkable is how automated this process has become. Part of the answer is orbiting 600 to 1000 km over our heads.

What have been the enablers of such a revolution? Before answering that question, we’ll start with a brief review of the transformation of the satellite industry over the last 15 years.

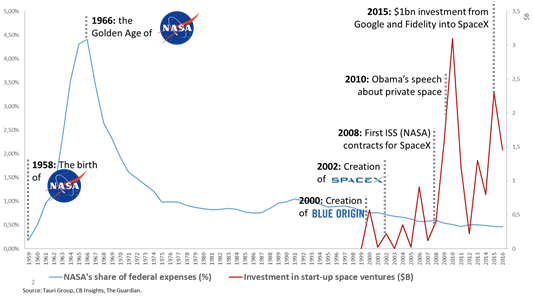

The rise in private space

Satellites technologies used to be funded by governments to develop military and then civilian applications.

A case in point that affects our daily life is the Global Positioning System (GPS), a Global Navigation Satellite System program that started in 1973, was fully operational in 1995, and opened to civilian applications in 2000.

However, budget constraints and geopolitical changes have impacted the public space funding. For example, the USA went from dedicating 4,3 % of their federal budget to NASA in 1966, mainly driven by the Cold War, to 0,5 % in 2017.

Standing in stark opposition of the public funding trends, we’ve recently witnessed rising interest from private investors to contribute to space technology development. The amount investors have poured into private space startup companies has literally skyrocketed in the past 15 years.

Source: Tauri Group, CB Insights, The Guardian

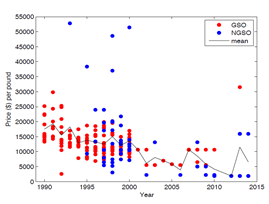

These investments have contributed (with the help of industrial space companies’ investments and public space agencies investments) to lower the cost of sending payloads into space by a factor of at least 4 in 25 years.

The price per pound of non-geostationary (NGSO) satellites has sharply decreased over the last 20 years.[1]

An impressive number of satellite constellations emerged, providing new telecom networks (such as Astrocast, which is developing a global machine-to-machine communication network at an extremely low cost), new positioning systems, and new image sources (such as Planet, which recently announced that it now releases updated images of the whole surface of the globe once a day).

New chips for devices have been developed to take advantage of multiple constellations and thus benefit from increased accuracy for positioning systems (such as Swift Navigation), for an extended coverage, lower cost or higher transmission speed for telecom applications.

What can we expect from the rising number of imagery satellites?

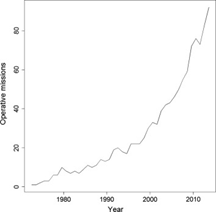

A rising number of satellites in space leads to a higher refresh frequency between two images. With a number of operative satellites that has been multiplied by 4 in 15 years, a daily refresh is not anymore something impossible, as proven by Planet.

The number of operative missions continue to drive the quantity of available images[2]

The decreased cost of launching and operating satellites, combined to the increased competition from satellites operators, drives down the price of satellite imagery. Beyond the free images provided by NASA and ESA, a high-resolution image (30 cm) is now usually priced in the 2 to 5$ / km², and continue to decrease by 8 to 10 % per year.[3]

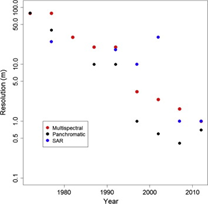

At last, the increased accuracy of sensors has been a key point in the improvement of image quality.

The image resolution of satellite has been multiplied by at least 20 in 25 years[4]

As a result, high-quality and recent images are likely to become a commodity.

If this prediction becomes a reality, what would prevent many industrial companies to take advantage of these new data sets?

From cheap images to affordable insights

Getting affordable images is a first step. Analyzing them at a reasonable cost is another one.

Highly skilled professionals called “photo analysts” have been doing this job for a long time, and are likely to continue to do it for highly confidential applications or where high levels of precision are required.

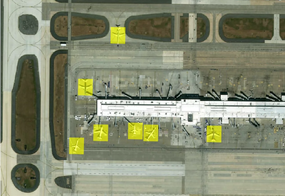

However, improvements in the application of machine learning technologies such as supervised learning create a new paradigm by enabling the automatic analysis of large sets of images, particularly in repetitive use cases where the algorithms can infer the presence of labelled objects such as airplanes (see example above) based on prior training data.

SpaceKnow is regularly analyzing 6000 industrial facilities China to create from scratch a China Satellite Manufacturing Index that many financial analysts have been chasing for years. Descartes Labs analyses thousands of acres of corn crops to predict US corn harvests.

Earthcube detects abnormal events in pipeline areas to prevent fraud and accidents.

And the list will continue to grow.

Why couldn’t we use images to monitor the construction status of a highway to objectively quantify progress against a performance contract, now that we can get one image a day?

Now that granularity is fine enough to detect roadworks (below 0.5m), why couldn’t we monitor changes in a road network via satellite instead of driving cars to maintain maps?

Why couldn’t we use satellite imagery to help auditors analyze an airline company by simultaneously counting airplanes at several airports worldwide, as shown in the picture above?

[1] 2015: Jack Yeh, David Revay, “Price per pound: a poor predictor for future growth in the satellite and launch industries. Understanding Moore’s law and future industry drivers”

[2] Belward A. & Skoien J., Who launched what, when and why; trends in global land-cover observation capacity from civilian earth observation satellites, ISPRS Journal of Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing, April 2014.

[3] Northern Sky Research

[4] Belward A. & Skoien J., Who launched what, when and why; trends in global land-cover observation capacity from civilian earth observation satellites, ISPRS Journal of Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing, April 2014,

[5] Courtesy of Digital Globe.

Why do we believe in Habiteo’s capacity to become a key player in the transformation of the real-estate sector?

Habiteo is a sales and marketing solution for real-estate developers. It helps them sell their properties faster by generating sales content (3D models, video clips…), and manage their workflow and sales process on different channels, to ensure a high-quality customer experience.

The company was created in 2014 by Jeanne Massa, after a very successful experience at TheFork (acquired by TripAdvisor) as COO. Denis Fayolle (CEO of TheFork) and Jean-Claude Szaleniec (ex-head of BNP Paribas Real Estate, ex-DG of BPD Marignan) also participated to the creation of the company and are still actively supporting the company.

While the old property market already started to embrace digitalization with websites such as SeLoger or ImmobilienScout24, the real estate development companies still use outdated commercial solutions, paper-based sales collaterals as well as paper contracts. Habiteo provides an innovative and unified solution that enhances the property development company productivity and eases the customer journey through the housing acquisition process.

The company has continously improved its solution and now supports more than 150 real estate-developers in their digital transformation.

A two-tier transformation of the real-estate sector

Digital trends affect homes. It may have started slowly with the first bulky and complex domotic systems, but the pace is clearly accelerating: a spate of connected products such as cameras or thermostats appeared on the shelves of all the DIY and consumer electronics shops. The US giants Amazon and Google have clearly stated their ambitions while launching their Home AI assistant: they want to become the brain of home.

The way people design their homes also changed. Social platforms such as Houzz or Pinterest have raised hundreds of millions with the promise of helping homeowners design their home by inspiring them with peers’ projects.

By contrast, real estate developers remained rather conventionnal in their approach in this rapidly changing environment. Most of them still propose more or less the same products than 20 years ago (with better energy-efficiency performances), at the same price if we put apart the variation in the real estate market, with the same customer experience.

First, the “one size fits all” strategy doesn’t work anymore. Acquirers wants to personalise their home design, and want to buy a property in a program that corresponds to their way of living.

Second, the battle for customer acquistion shifted online. While most of the sales process was done in pop-up stores (or agencies) located close to the future real-estate programs, customers are now looking for their homes online.

Nascent real-estate developers such as Habx or Buildrz in France started with a clean sheet, and the ambition to build a real-estate developer 2.0: online targeting of customers and online sales, connected homes, home personalization, etc. The growth challenges remain important for new entrants, such as cash constraints and the complexity to source new projects and to develop them quickly.

At Aster, we do think that Habiteo has a key role to play to transform the way real-estate developers sell homes, by mastering the digital experience they offer and eventually drive a transformation in the industry.

The promoters will have to adapt their customer experience to the digital natives

As for the car-retail market, most future buyers start their quest for the perfect home online. After a long screening on the internet, most of them have a clear idea of what they would like to buy before going to the local shop dedicated to a specific program. In other words, quite a big chunk of the sales process is now online. In other words again, targeting the right customers at the best cost online, and bringing them the best quality content to attract them becomes key in the sales process.

That’s where Habiteo started 3 years ago. Since then, the company never stopped to increae the visual quality of the 2D views generated for 2D plans, and innovate continuously with virtual vists, flat-configurators, etc.

A home purchase is not like any other purchase. There is no doubt that part of the process will stay offline. But the role of the real estate pop-up stores or agencies changes. These spaces, initially dedicated to the information of potential acquirers and to the signature of paper-based documentation, are turning into experience spaces, where the end-game is first, to confirm the impression of the potential acquirers about the reliability and the quality of the real estate developers, and second, to help the potential acquirers feel the atmosphere of their future neighboorhood. Digital technologies such as Augmented Reality might help, but the main challenge will be to create a true omnichannel experience for the future buyers. Know your customer before he gets in, know his doubts, where he is in his buying process, in order to provide him with a best-in-class customer experience.

Habiteo has helped more than 150 developers in this journey. It is by far the clear leader in France and the company succesfully started an expansion in Europe with first projects in Spain and UK.

Such a company, participating to the digital transformation of a traditionnal sector with internationnal ambitions, fits perfectly our model. Our goal and mission is now to act as a catalyst thanks to our ecosystem of industrial partners providing access to preferred markets, and to facilitate Habiteo’s geographic expansion with support from Aster’s various branches around the world (San Francisco, Beijing, Tel Aviv, Nairobi and Paris).

The open source concept, inspired by the libertarian and anti-capitalist ideals of free software, may not seem to be a prime concern for industrial firms in the transportation sector. As the value chain in that sector prepares to undergo significant changes, these firms could be very tempted to hold on tighter to their patents and data. But we believe that, on the contrary, a targeted open source strategy can lay the groundwork for firms to gain a decisive competitive edge.

Embracing the open source philosophy: community creation and sharing of standards

The open source tradition started a new conversation about tapping more talent through crowdsourcing and unleashing synergies between different sectors and types of expertise. By way of example, Local Motors developed and marketed the Launchforth design platform, through which 70,000 members have co-developed 7,500 products. It brings carmakers and the developer community together through challenges. Domino’s Pizza received 441 design submissions for its delivery vehicles. The $40,000 price corresponded to the transfer of the intellectual property from the community to Domino’s Pizza.

By facilitating co-development, collaborative tools encourage the pooling of R&D costs and the tapping of talent from new fields (big data, artificial intelligence, Blockchain, etc.). Supported by micro-factories, community creation allows rapid iterations between developers, suppliers and end-clients, saving valuable weeks in the process of developing products and bringing them to market.

XYT is a company with a model that is also close to the open source world, and it illustrates another of its advantages. This Paris region-based startup holds IP rights for the standard, approved utility vehicles it sells. Its customers can customize the vehicles to suit their own needs. XYT is therefore creating a marketplace for community-developed accessories. This approach, which moves away from the traditional value chain, has won over Japan-based glassmaking giant AGC, which sees in it an opportunity to learn more about those who buy its products.

Adopting a targeted but resolute open source strategy is now a necessary step in the quest to share standards and reach critical mass

In July of 2017, Chinese search engine Baidu launched Apollo, a platform that provides autonomous driving software to all players seeking to develop their own systems. It makes available to a community the source code allowing partners’ vehicles to detect obstacles, plot courses and maintain control. The stated goal is to test its operating system as broadly as possible under real driving conditions in order to rapidly collect data that can be used to improve it.

It is urgent for industrial firms from the automotive and transportation sectors to start openly using the same resources rather than hiding behind their patents. Tesla set the example in 2014 when it made its patents public. This was a strategic decision intended to lay the groundwork for the electric vehicle market to boom, since it promoted the emergence of a standard for charging infrastructure. Indeed, the market cannot take off if this infrastructure is not quickly put into place. Ron Adner and Rahul Kapoor reiterated this in a recent article in the Harvard Business Review: “It may pay to focus a little less on perfecting the technology itself and a little more on resolving the most pressing problems in the ecosystem.” By giving up the exclusivity associated with its patents, Tesla made a fundamental tactical step toward standards adoption and critical mass.

In more general terms, industrial firms can use open source strategies as a spearhead in the fight against digital platforms. In his article Les communs, l’open source, les objets liens et l’Art de la Guerre, Gabriel Plassat is as clear as can be: “Industrial alliances must thus develop their own digital community platforms to provide a variety of stakeholders with the bricks needed for innovation and to catalyze distributed innovation. It is no longer an option.”

With €240 million in capital raised, Aster takes position as the leading venture capital fund dedicated to the energy transition and the mobilities of the future. The investment company brings its total funds under management to €500 million.

A €240 million capital increase operation to be invested primarily in Europe and the United States

The €240 million in capital raised in the first closing by several industrial players will be used to finance companies at all levels of maturity. Investments will range from €250K at the seed level to €15M in the growth segment.

Jean-Marc Bally, Managing Partner at Aster, shared his delight “with this remarkable operation, which proves all the confidence our subscribers have in Aster’s unique model and in the vitality of venture capital in France”.

The funds will be invested primarily in Europe and the United States, with potential for action in Asia. Aster covers all the world’s major innovation hubs, with offices in Paris, San Francisco and Tel Aviv, as well as a presence in China and Africa, through partner funds.

Two key topics: the energy transition and the mobilities of the future

Aster’s investments will be focused on the digital and industrial transformations of the energy and mobility markets, the team’s areas of expertise for the last 17 years.

The energy transition will be the first development line. The second angle for investment will be the mobilities of the future, in particular: new usages; technologies and infrastructures fostering sustainable mobility and multi-modality; and connected and autonomous vehicles.

According to Fabio Lancellotti, Partner at Aster, “the transformations underway in the energy and mobility value chains are creating opportunity for budding companies, as well as for industrials. We want to energise the sector by combining our strengths through our ‘Business Hub’ approach”.

A “Business Hub” to boost start-up projects

Aster provides the funded companies with an acceleration platform, facilitated by a dedicated team which mission is to encourage business opportunities. Thanks to its “Business Hub” approach, Aster provides support to entrepreneurs at all stages of their projects and enables them to reach the most relevant players, networks and markets for their development.

Over the last twelve months, the “Business Hub” has enabled more than 500 contacts and generated around twenty partnerships between start-ups and industrial players.

The ways that we interact with computers are poised to change nearly as dramatically in the coming decades as computers themselves have over the past several decades. We’re in the early stages of an evolution from highly complex, techno-centric approaches to much more intuitive, anthropo-centric interfaces. The coming changes will almost certainly impact the way companies do everything from operating industrial equipment in their own production facilities to designing the products that they sell to customers. Here we have sought to outline our view of the current landscape and emerging technologies, relevant companies and the use cases that they’re enabling.

The term Human-Machine Interface (“HMI”) describes the methods in which people interact with computers, and is a subset of the broader User Interface (“UI”) field. This includes independent components and as well as unified systems which encompass:

- Input technologies such as gesture recognition, eye tracking and voice control

- Output technologies such as ultrasound, electro-tactile stimulation, and vibrotactile stimulation

- Analytical techniques such as Machine Learning & Natural Language Processing

- Unified systems which combine those technologies such as Augmented Reality (“AR”) & Virtual Reality (“VR”). Note: we have chosen to focus on AR technologies here. Many of the component technologies we’re discussing have applications in both AR & VR, but they are distinct ecosystems that are seeing interest from very different user bases. Even though “AR/VR” are commonly lumped together as a single topic, we try to avoid making a similar comparison.

The QWERTY keyboard, first developed in the 1870’s, was one of the first attempts to mechanize input from an individual user into a medium that could be stored & shared by many in the future (a letter or book). Designed to avoid routine collisions between keys which slowed typing speeds, it demonstrates the type of technological barriers that were a focus in early HMI solutions. These early approaches required the user to adapt their behavior to fit the machine in ways that were unnatural at best, and highly complex at worst. From punch cards to keyboards, the use of these technologies was reserved either for specialists or for those that specifically acquired a specific skillset (remember typing classes?).

The second wave of HMI kicked off in the early 1990’s, at which point GUIs and display technology had developed sufficiently to allow touch screens to be introduced. This was the first time that the medium through which humans communicated with machines became transparent: the combination of input & output mediums into a single interface gave users the impression that computers could understand human touch & motion the same way other humans do, without requiring a foreign object to mediate the process.

The dramatic decline in the cost of computing driven by consistent innovation in semi-conductors and followed by the smart phone revolution has led to the proliferation of small yet high-powered computers with high-bandwidth connections nearly everywhere that they can be useful to humans today. The lack of space that accompanies a traditional stationary computer (i.e. your desk!) and the capability of the latest computers have simultaneously required and enabled new, intuitive user interfaces to be developed.

Why does this matter?

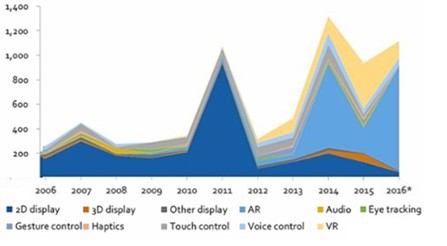

The aforementioned changes have not been lost on those with large pools of capital to invest, and both venture capitalists and large tech corporations have not been shy about placing bets in the HMI space. VCs have invested more than $1bn per year into HMI technologies for each of the past three years. Following a brief investment spurt into 2D display companies in 2011, excitement about AR (and VR, although to a lesser extent) has accounted for the clear majority of inflows into the space.

Major tech corporations have also been reasonably active making acquisitions, albeit with a preference for earlier stage companies to bolster their technology portfolios and talent pools. Intel (Omek and Indisys), Apple (VocalIQ), Google (Flutter), Freescale Semicondutor (Cognivue), and Facebook-owned Oculus (Pebbles Interfaces) have all targeted HMI startups in sub-$100m transactions.

Applications of HMI in Industry 4.0

Lots of attention has been focused on the application of HMI technologies in consumer use cases like virtual assistants. Instead of repeating that message, we will focus on a few specific applications which are impacting industrial companies.

Industrial machine control is an obvious area of focus. The machinery utilized in industries ranging from oil & gas to healthcare is often plagued with archaic user interfaces which can reduce productivity on the machines which are commonly amongst the most expensive in the facilities where they’re located. Integrating state of the art HMI into these assets can create new efficiencies on many levels:

· Machine operators benefit from receiving physical feedback from haptic technologies, or as wearables or AR glasses free their hands and attention to focus on their primary task. New levels of safety are often achieved, which is far more important than efficiency ever will be.

· Maintenance professionals can quickly visualize machine status in real-time, enabling them to prioritize their workload and anticipate tooling and material requirements for individual tasks. Remote collaboration also allows off-site specialists to consult or guide local technicians through tasks that would require travel otherwise.

· Managers are empowered to quickly survey the status of all operations inside a given plant or facility and receive immediate notification when potential bottlenecks arise.

Across these categories, deployment of advanced HMI technology can help attract young people to join an aging workforce (a trend which is consistent with all Industry 4.0 tech).

The automotive sector has also become a rapid adopter of new HMI technology. Automakers all strive to deliver a differentiated UX that breeds demand for a given brand/model. New HMI technologies are most commonly found in the infotainment systems of high-end models, but the redesign of mundane features like door openers has also demonstrated their applicability.

Touch screens and gesture recognition technology have emerged as favorites for automakers. You’ve likely noticed that the touch screen in your car isn’t as sleek as the one on your smart phone. This is because automakers have favored resistive displays over the capacitive screens found on most phones. The long design cycles (7–10 years), the need for longevity (12 years, 200k miles), and the intense focus on cost all factor into a slow rate of adoption of new technology. However, suppliers like Continental are working to commercialize infrared screens. Infrared sensors are also being evaluated to monitor driver attentiveness in Advanced Driver-Assistance Systems.

Basic gesture recognition sensors are also being applied for tasks outside the car. Drivers approaching their parked Ford Escape with an armful of groceries can now open the tailgate by passing their foot underneath the rear bumper instead of setting down what they’re carrying.

Advertisers are also adopting new gesture recognition and eye-tracking technologies in Digital Out of Home (“DOOH”) advertising. Digital displays are more expensive to deploy, but have been shown to drive 2.5x more revenues per incremental dollar spent. The most advanced ad displays enable a wall-mounted advertisement to become a point of sale. In other cases, they can allow a viewer to access additional content related to the ad via an app download or launching a website from a QR code. Higher engagement combined with new analytics which enable advertisers to target precise groups of users have resulted in new revenue for both media companies and their customers alike.

Conclusion

Many of the use cases identified here may not feel like they’re on the cutting edge of technology in today’s internet age. However, the computerization of industry and manufacturing is one of the key theses underpinning the Industry 4.0 trend. As such, the integration of technologies being utilized in consumer electronics would drive a significant investment and productivity boom, and that’s to say nothing about the potential of state-of-the-art technologies currently in development.

The design and replacement cycles for the types of large physical assets we’ve covered are certainly longer than those in the consumer electronics industries. However, the highly capital-intensive nature of the industries that are being transformed means that dramatic improvements in cost structure and new revenue generated through operating efficiencies are possible.

Please find here the french version.

A subway that runs at the speed of sound? That’s the bold claim made by Canadian startup TransPod when speaking to a room full of inquisitive journalists, students, venture capitalists and industrialists at the Arts et Métiers Hotel in Paris on June 20. Founded in 2015, TransPod is expounding upon the Hyperloop concept with hopes of reshuffling commercial transit maps starting in 2025.

A new mode of transportation to compete with planes and trains

TransPod is taking on Elon Musk’s widely publicized concept whereby pods are propelled over layers of air through a partial-vacuum tube claiming it can correct its presumed flaws. For example, instead of shooting the pod through a tube at 10 Pa, it wants to raise the pressure to 100 Pa to streamline the infrastructure, even if it means increasing the per-vehicle energy consumption. Another preference that sets it apart from competitor Hyperloop One is that TransPod is developing an active levitation system that would reduce jerk for better passenger comfort.

The goal is to build an interurban transit system of pods that can accommodate roughly 30 passengers and travel at speeds of up to 758 mph with a lower carbon footprint and ticket price than airplanes. They have been looking at a link between Montreal and Toronto. TransPod also believes its system would realistically be able to compete with road freight on heavy traffic routes.

In 2016, TransPod raised $20.2 million in seed money from the Italian investment fund Angelo Investments and began talks with transit agencies and industry players for a Series A round of $50 million that could become a reality this fall. The company plans to have prototypes ready in 2020 and be fully operational between 2025 and 2030.

From futuristic concept vehicle to resilient mass transit system

It is hard not to admire the determination of TransPod’s founders to get their idea off the ground and forge partnerships between industry and the financial world. But there still remain open questions on the system’s technical and economic viability. Their answers to audience questions on that balmy June evening were not always reassuring. For example: When traveling at a speed of 758 mph, can you ensure a 90-second headway? Could passengers withstand deceleration in case of emergency braking? How to manage pods U-turn at the end of the trip?Who will fund the infrastructure?

Indeed, speed isn’t everything and TransPod is realizing that the propulsion breakthrough requires many other not-so-sexy inventions like reasonable ways to evacuate passengers if the system goes down. This lack of a systemwide view is a peculiarity we often see in startups proposing disruptive transportation technology: SeaBubbles definitely hit Viva Tech by storm when it unveiled its first bubble, but now it has to come up with a turnkey system that includes charging and special safety docks designed for mass transit; skyTran, whose two-passenger monorail pods were supposed to crisscross the skies of Tel Aviv, didn’t take off. Its founder, a NASA veteran, may have overlooked the fact that while an Apollo mission only has to work perfectly once, a public transportation system has to operate flawlessly and safely millions of times.

That’s in contrast to the rail system — and its trusty sidekick the wheel-on-rail principle. Though often chided for being stuck in the past, its undeniable decades of experience regarding operation and degraded modes management operating a system are the cornerstone of a resilient and sound public transit system.

Thus, in an environment where vehicles like buses and subways have virtually become commodities, the know-how integrators have about operating a mass transit system over time seems to be a majordifferentiator. Yet like all legacy businesses, they struggle to innovate.

What’s inspiring about TransPod’s venture?

A healthy dose of skepticism about the Hyperloop system isn’t actually a valid reason to throw the baby out with the bathwater. Like TransPod CEO Sébastien, who humbly considered people’s comments so he could improve upon his idea, let’s focus on how we can be inspired by TransPod and others.

To begin with, the few million dollars they raised should enable the startup to complete some work packages. Its main advantage is to start from scratch, whereas traditional manufacturers have to deal with a legacy wich is both treasured and unwieldy. TransPod CTO Ryan doesn’t get bogged down in the principles of railway signalling. He catapults himself into a world where pods will be communicating with each other through artificial intelligence and veillance flux. Some compelling technology bricks will likely emerge from this R&D.

Next, TransPod is managing to attract industrials that probably see it as an opportunity to design out of the box. For example, Liebherr-Aerospace has just signed a contract to engineer the cabin system and IKOS is taking over the propulsion system. This deserves recognition at a time when corporates struggle to implement successful open innovation models.

Lastly, the way TransPod is insisting upon passenger experience may not just be a tactic to hide its technological flaws. The approach reminds us how fundamental it is to tease riders. if we want mass transit system to remain the backbone of mobility in the future.

From that perspective, it’s easier to understand that the two worlds mentioned here — startups with futuristic transportation projects and conventional mass transit players — are more complementary than adversarial.

True disruption probably lies at their crossroads.